Media Releases

Insights from Cyberpunk creator Mike Pondsmith

Media Releases

We ponder questions on Cyberpunk 2077 and the challenges of working with intellectual property. Thankfully, Mike offers some answers.

The Singapore campus of James Cook University has a passion for video games — whether it’s grooming new creators in our Game Design courses, or celebrating and preserving the history of games in our Retro Inspired event .

As one of the most anticipated video games right now — Cyberpunk 2077 — draws closer, we invited the creator of the Cyberpunk pen-and-paper RPG himself, Mike Pondsmith from R. Talsorian Games, to speak at a Public Lecture in Retro Inspired.

James Cook University in Singapore was happy to sit down with Mike Pondsmith, who was able to share more about multimedia, the challenges of working with intellectual property, and Cyberpunk 2077.

(Pictured: Mike Pondsmith)

(Pictured: Mike Pondsmith)

How do you know if an intellectual property (IP) has the potential to go to other mediums?

Some ideas work great in a book but would make a terrible movie. For example, Starship Troopers. It’s a classic. Every young person I knew at some point read Heinlein and read starship troopers. But it makes a terrible movie.

I remember Edward Neumeier who did the screenplay for it, he said, “Yeah, my problem was that most of Starship Troopers is Robert Heinlein talking about the philosophy behind that world, it’s not about people landing and fighting bugs.”

So I’m sitting here saying, “What did you do?”

“For starters, I decided I was going to focus on that one small love story idea, and the next thing we know we had Archie, Betty and Veronica going to outer space and kill bugs.” That didn’t do the best for starship troopers, but they made money.

Other things, like Dragon Ball? They’re made to be done in games. The creator, in this case, knew the other areas he was going to want to take his piece. And he built those things into the IP. So when you are thinking of a video game you are working on, particularly if you’re directing the IP, you should also be thinking “How is this going to adapt somewhere else?” When they want to make a movie, how do they make that movie? How will I adapt my idea, my concept, to go to other places?

When you’re adapting a property to different mediums, what are some of the most important aspects of it to ensure that it makes that transition smoothly?

You need to look at two things.

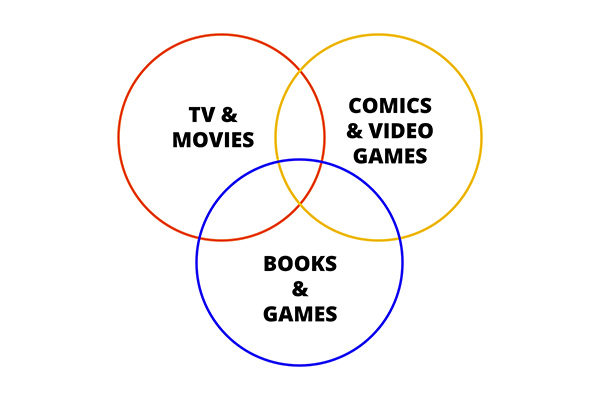

One is what your audience will really be. It’s a big Venn diagram. It’s basically: who are the people who are in your audience? You can’t assume they will always be the same people who are your audience for [for example] the video game.

Sometimes, you’re able to work it so they will be, or you bring them into your area. For example, by having 2077 rooted in 2020, we have a lot of people who are excited for the video game now excited for the tabletop games as well, because we’ve shown that kind of connection.

The second thing is to know the mediums, and how they best describe or show the property. And that’s a real tough one. Each one of them has strengths, and each one of them has weaknesses.

If I’m looking at a movie, I’m looking at a lot of visual that’s fed to me. I get story, but I don’t affect that story. TV and movies are what are called hot media.

Comics and video games are more interactive. One reason is, with comics, you have to invest in the stories, the characters, the arc; you have to know many things about that media to enjoy it. A video game, you have to know it, you have to be able to play it, interact with it, you make choices, you move that media towards what’s called cold media — where there is a greater investment by the person consuming it.

Books and [tabletop] games, they’re cold media. They take the largest amount of investment from your audience. Your audience, in many cases, has to make the story up around Battleship [for example]. In books, they have to imagine Harry Potter. They have more to fill in, so their interactivity is higher.

Here’s the problem: when you’re doing that — if I, for example, picked up Harry Potter, I’m used to people who are going to be wanting to see stuff they saw in their own heads. So if I’m doing a video game, Hogwarts has got to look a certain way — it’s got to look the way that people who were invested saw it. Close enough, at least, so that people don’t go, “Oh man, they screwed it up, I’m never seeing that again.”

The Johnny Silverhand that we have in ’77 is different than the Johnny Silverhand I wrote about in 2020. But that was a Johnny Silverhand that was, at that point, 22 I think. Lots has happened since that time. And we talked a lot about “Okay, what happened to Johnny during all this? What was he doing? How did this plotline come together?”

Do you have the story mapped out beyond Cyberpunk 2077?

I do. I actually know where everything’s going to go and how it ends up.

Usually if you get into a game, what you see is what you get. But in this case, what you see is just the beginning.

We have a lot more options than you would normally have in a regular RPG (role-playing game), because a regular RPG is going to be limited by what you can show in the game.

Have you thought about making books or movies set in the universe of Cyberpunk?

We’ve actually done that in the past, and now we’re hoping to rethink it. Actually, there’s a whole series of books. They were done by Time Warner Aspect back in the ‘90s. So we’ve done the book thing.

The difference is that we now have more writers, and we’re working with the CD [Projekt Red] team. And we have an interesting thing because we cover everything up to about 2060, and then they pick it up from there. So we’re still working out if we do novels, where do we put them.

Well, earlier you mentioned you’ve planned ahead beyond ’77. Are there plans to expand this franchise so that it goes into other mediums as well?

Well, I can’t really speak to it exactly because, one: I’ve got NDAs; but also: we don’t know.

Here’s the thing: you do a new game, you expect it’ll do well, but you don’t make too many plans because if you do, it might be bigger. When we started this, nobody in the team went, “Oh yeah, we’ll get Keanu Reeves!” We were thinking if we get the guy who voiced Geralt [in the Witcher video game series], that would be cool.

Because game development is iterative, there’s a lot of things you don’t know. When you finish the first project, you start figuring out what you’re going to do with the second. We have always assumed, at Talsorian and I assume at our partners at CD, that we want to get movie and TV.

You always hope to have whatever you’re doing expand to other mediums, if you can do it right. If you do it badly, the next thing you know, you’ve killed your golden goose.

Where do you draw your inspiration from to build out these worlds and stories?

I always liken being a game designer to basically eating a pound of dough, couple gallons of tomato sauce, whole pepperonis, can of mushrooms, and maybe two pounds of cheese, and then throw up a pizza.

Which is to say, you take a lot of different things from all over, and you have to put them into a coherent whole.

You take from all the stuff in your life, and you try to put a narrative together for it. And the narrative — it’s important to put something together that people have hooks into, that they understand, and can really make it part of their own perception.

The original Cyberpunk was influenced by ‘80s pop culture. In 2077 and what you’ve planned ahead for, are there any specific elements from current pop culture that you’re drawing from?

The weird part is that all that retro-culture stuff that was ‘80s culture, it’s back with a vengeance. Like OutRun, for example, which has a particular style — ‘80s art — that’s almost defining Cyberpunk now. Jackets with the high collars, the huge guns, that’s still pretty darn ‘80s. What’s happened is that it’s gone through so many years that people can look back on it and go “Yeah that was kind of cool, let’s just do some of it again.”

So part of it is we ended up having to go back, stylistically, a bit to the ‘80s, because the genre feels that way now anyway. And where we varied it was looking at where certain things that we have now would extrapolate to.

In the ‘80s, we didn’t have cellphones that did everything for you; cars were somewhat different; certain styles were different. We didn’t make certain assumptions about how people lived or dressed. Now we have to take those into account, to make it relatable to the people who are going to be buying the game. They didn’t grow up in 1980, it’s not like their culture. But they rediscover it.

I found that it was better to keep the right look and feel than it was to update things just to be current, because people had a certain set of expectations.

This interview was edited for clarity and brevity.

Check out more photos of the 5th Annual Retro Inspired event, here.

Find out more information about our Games Design courses here.

Contacts

Media: Pinky Sibal pinky.sibal@jcu.edu.au